In a friend of the court brief bound to raise state attorneys’ eyebrows throughout Florida, the Florida House is arguing that prosecutors have no discretion with regard to capital punishment, that the state Legislature’s intent was to rest all discretion with juries.

The House filed the brief in the Florida Supreme Court case of Orlando’s State Attorney Aramis Ayala versus Gov. Rick Scott. The issues, in that case, are whether prosecutorial discretion gives Ayala the power to refuse all capital punishment prosecutions, as she’s done; and whether the governor has the right to strip capital cases away from her, as he’s consequently done.

The brief, filed late Wednesday, argues that a state attorney is not the one to decide on death penalties. It contends the state attorney’s role is more clerical, to review facts of a case to determine if aggravating circumstances exist that could merit a death penalty, and then leave the decision of death or life in prison entirely up to the jury.

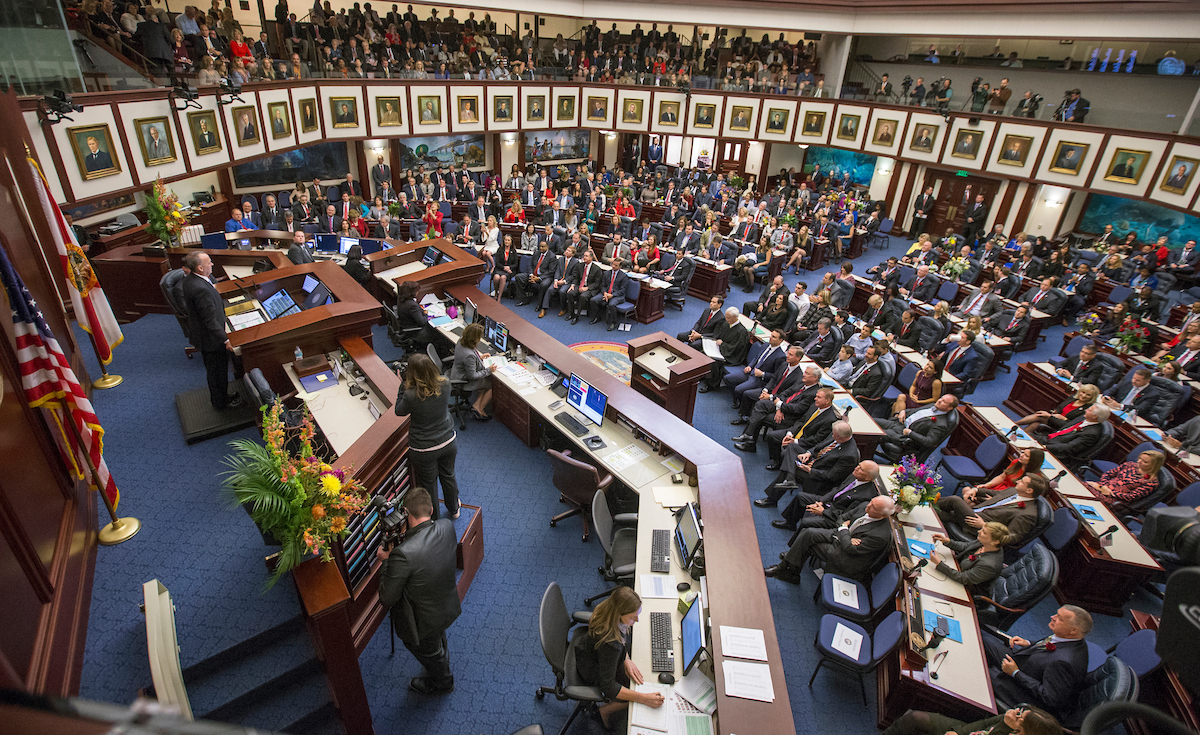

The House of Representatives is one of the numerous bodies filing amicus curiae briefs in the case, indicating the enormous ramifications the legal battle holds for prosecutors, the governor, and the Florida Legislature. Among others expected is a dissenting brief from several Democratic members of the House and Florida Senate.

The official House brief declares, “the policy of this State, reflected in legislative enactments, reserves to the jury — speaking for the community and reflecting that community’s values — the threshold decision whether death should be an authorized punishment for a capital murder conviction. A state attorney, by contrast, has no authority to abrogate the Legislature’s death penalty policy within her circuit.”

Ayala’s lead attorney, Roy L. Austin Jr., called the House argument “stunning.”

“This is a stunning position that calls for an unconstitutional interpretation of the Florida statutes, not to mention contradicting the positions and pleadings from the governor, the attorney general, the FPAA and every state attorney in Florida,” Austin said in a written statement to Orlando-Rising.com.

On March 16, Ayala, the newly-elected state attorney for Florida’s 9th Judicial Circuit, covering Orange and Osceola counties, announced that she had reviewed Florida’s laws, court decisions, and the opinions of various parties to conclude that Florida’s death sentence law was not just for anyone, so she would not use it. Scott responded by stripping 23 cases from her and reassigning them to State Attorney Brad King of Florida’s 5th Judicial Circuit.

Ayala sued, both in the state Supreme Court and in U.S. District Court, asserting her rights under the doctrine of prosecutorial discretion, and challenging Scott’s authority to reassign cases if she had not violated any laws.

At issue in most of the filings so far is whether prosecutorial discretion could be exercised before or after Ayala or any other prosecutor reviewed all the facts of the case and weighed aggravating and mitigating circumstances.

But the House argued that the prosecutor does not have discretion, even after he or she reviews the facts of a case. That could fly in the face of the common practice among prosecutors, who often weigh a number of factors, from victims’ families desires to potential plea bargains, in deciding whether to pursue death penalty prosecutions.

In the brief, a section title lays it out bluntly: “The Legislature’s capital sentencing scheme leaves no discretion to the state attorney to assess whether death should be an authorized punishment in a capital murder case.”

In another argument that may make state attorneys uncomfortable, the House also challenged the independence of state attorneys.

Citing a 1939 Florida Supreme Court Decision and several statutes, the brief argues that a “state attorney in this State is not merely a prosecuting officer in the Circuit in which he is; he is also an officer of the State in the general matter of the enforcement of the criminal law. … It is the State, and not the County, that pays his salary and official expense. And when a state officer like the petitioner refuses or is unable to follow the State’s policies as set by the Legislature, the Legislature fairly can expect that either the Governor, or a chief circuit judge, will find someone who will.”

One comment

Ray Roberts

May 4, 2017 at 3:23 pm

Was this “brief” voted on by the House?

Comments are closed.