Did a congressional map Gov. Ron DeSantis demanded lead to the gains enjoyed by Republicans in Florida’s House delegation? Maybe not.

A new analysis from MCI maps shows Republicans may have performed as well in House races under a less polarizing map produced by the Legislature — at least during a landslide year for the Florida GOP.

In fact, Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, the only federal candidate running statewide this year, won the same number of congressional districts under the map signed by DeSantis as he would have under every map considered by a full chamber of the Legislature.

That doesn’t mean the map was meaningless. It likely cost U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, a Tallahassee Democrat, any chance at re-election. At the same time, the DeSantis map may have inadvertently saved U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor, a Tampa Democrat, from a competitive election cycle and likely defeat.

Coloring the lines

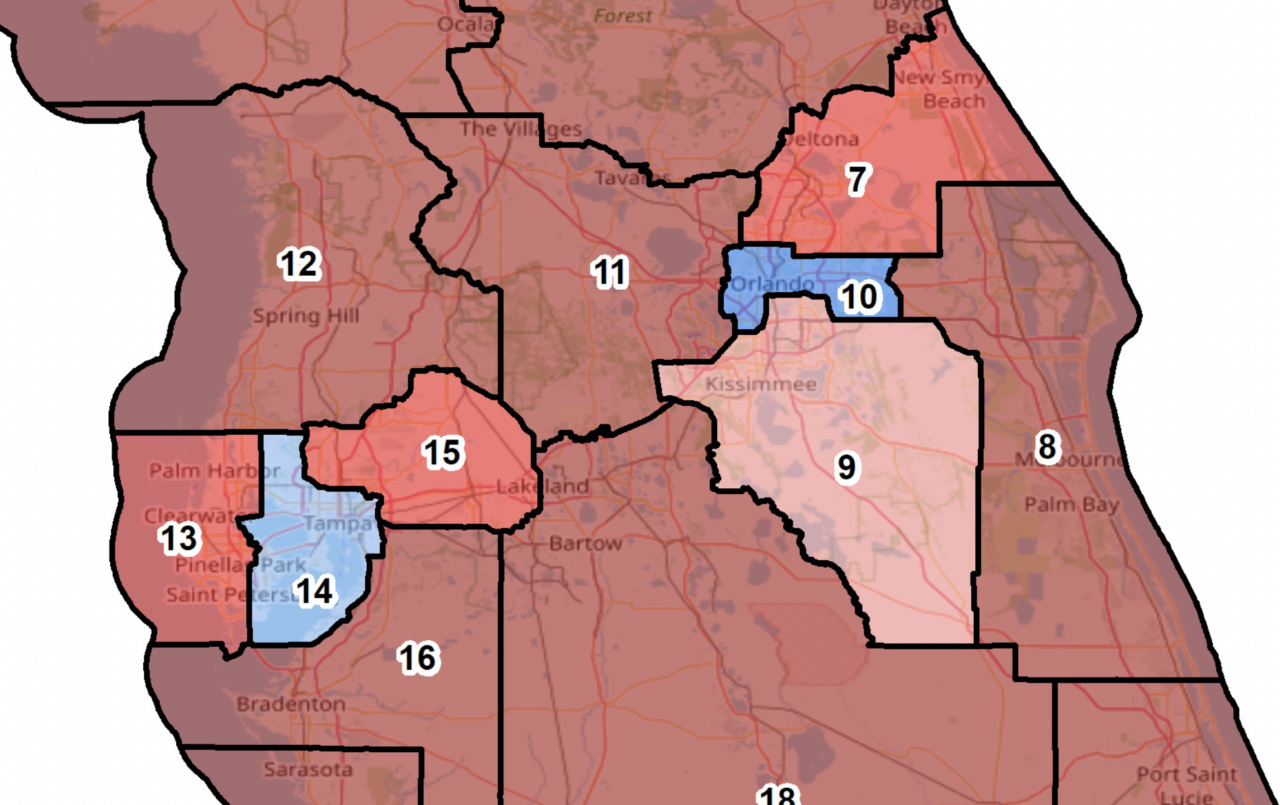

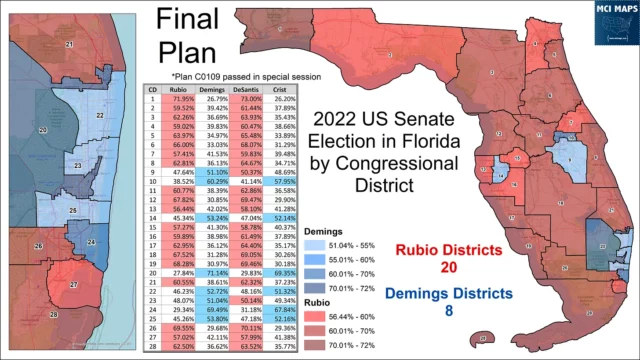

Under the map signed by DeSantis and produced by his own staff, Republicans performed incredibly well. When a new Congress takes office in January, Florida will send 20 Republican U.S. Representatives to Washington and just eight Democratic Representatives.

By comparison, Florida’s outgoing House delegation includes 16 Republicans and nine Democrats, with two additional seats formerly held by Democrats vacant. Florida picked up a House seat based on the 2020 Census, so under the new map, the GOP won the extra district and flipped three seats previously held by Democrats.

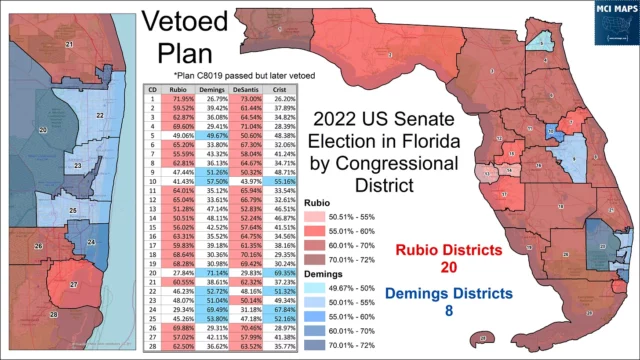

But DeSantis’ map was approved only after the Governor vetoed a map produced by the Legislature. DeSantis considered the lawmaker-made map to be a racially motivated gerrymander, but critics assert DeSantis wanted a partisan gerrymander that would maximize Republican gains.

Civil rights groups have sued the state over the cartography in state and federal court for allegedly violating Florida’s Fair Districts constitutional amendment and the Voting Rights Act.

How would Republicans and Democrats have fared under the vetoed map? Well, the one federal race held statewide this year at least offers a hint as to whether voters in different pockets of the state prefer a Republican or a Democrat representing them on Capitol Hill.

Rubio in November won re-election over Democratic challenger Val Demings with a dominating lead of nearly 17 percentage points. Of note, Demings won the vote in eight of 28 congressional districts under the new Florida map, the same eight districts where Democrats won congressional contests.

Overlaying the results of the Rubio-Demings contest to predict outcomes is arguably an imperfect model. Candidate quality varied seat to seat. The Democratic candidates who won each of the eight blue House districts all outperformed Demings. Rubio won 20 districts, but was outperformed by the winning Republican House candidate in 16 of those jurisdictions.

Other factors also make comparisons difficult. Florida elected six freshman House members this year, all in open seats, while Rubio secured his third term in the U.S. Senate.

Still, the parallel between U.S. Senate candidate performance in the seats shows the race may be the best indicator of voter sentiment in each district as far as which party should represent the region in Congress.

Of note, DeSantis, who also won re-election in November, won in two congressional districts where Rubio lost and voters elected a Democrat to the House. Those include Florida’s 9th Congressional District, where U.S. Rep. Darren Soto won re-election with under 54% of the vote, and Florida’s 23rd Congressional District, where Democrat Jared Moskowitz won with less than 52% of the vote.

Demings won in CD 9 and CD 23 with just over 51% of the vote. But DeSantis took just over 50% of the vote in both seats in the Governor’s election, which he won statewide by 19 percentage points over Democrat Charlie Crist.

Vetoed map

As for how things would have turned out under different cartography, the MCI Maps analysis shows Rubio also won 20 of the proposed districts in the vetoed map from the Legislature, and that Demings also won eight seats. But the places where Democrats proved most successful look different under that map than the one signed by DeSantis and used in the General Election.

Notably, DeSantis took the greatest issue publicly with a North Florida district he considered a racial gerrymander, one represented now by Lawson.

Under the DeSantis map, Lawson chose to run against U.S. Rep. Neal Dunn in Florida’s 2nd Congressional District. He lost in Florida’s only incumbent-on-incumbent U.S. House race. Republican Aaron Bean won in Florida’s 4th Congressional District, a GOP-leaning successor to Lawson’s old seat.

But in the Legislature’s map, lawmakers had crafted a Jacksonville-area seat in an attempt to assuage DeSantis’ concerns about a sprawling Tallahassee-to-Jacksonville seat, while leaving intact a Duval constituency whose Black voters arguably controlled the outcome of any election.

While Lawson criticized the Legislature’s map, the MCI analysis suggests he may have won the proposed Jacksonville-area seat. Demings beat Rubio there by less than a percentage point, though DeSantis did outperform Crist. That suggests that in a federal election, a Democratic congressional incumbent would have faced a close race but one where he was favored to win.

Elsewhere in Florida, the DeSantis map changed the makeup of two Central Florida seats from jurisdictions where Democrat Joe Biden won the 2020 vote to seats where Republican Donald Trump had more support.

Florida’s 7th and 13th Congressional Districts are now represented by retiring Democrats — U.S. Reps. Stephanie Murphy and Crist, respectively. Neither incumbent sought re-election, and the seats were won in November by Republican Rep.-elects Cory Mills and Anna Paulina Luna, respectively. Rubio and DeSantis also won both seats.

But the MCI Maps analysis shows Rubio would have won both CD 7 and CD 13 under the Legislature’s map as well. The same goes for DeSantis. Both districts would have voted for the Republican statewide candidates by more than 10 percentage points, assuming a different congressional map generated no consequence to statewide races.

That suggests that even without the changes pushed with DeSantis’ cartography, Republicans likely would have won both seats regardless.

The map produced by the Legislature also shifted CD 7 to a Trump seat. But a map approved by the Senate but never the House, and which the Democrats ultimately embraced as the most fair map considered in Florida, left that Orlando-area seat as Biden country.

Nevertheless, MCI Maps data shows Rubio and DeSantis won the district anyway. At least in a year when Republicans overperformed statewide, the choice of maps appeared to deliver little impact in outcomes.

On the other hand, Democrats may have been in trouble in another Tampa-area district had the Legislature’s maps stuck.

Under the DeSantis map, Castor easily won re-election in Florida’s 14th Congressional District with nearly 57% of the vote to Republican challenger James Judge’s 43%. Both Rubio and DeSantis lost in CD 14 under the Governor’s map.

But under the Legislature’s vetoed map, Rubio won close to 51% of the vote in that district, and DeSantis won nearly 53%. That suggests that if Castor’s district remained a Hillsborough County-contained district instead of being redrawn as a Democratic vote sink absorbing the bluest parts of Pinellas County, Republicans could have retired the Democratic incumbent in November.

Fair comparison?

So, are the results in statewide races clear indicators of how voters in hypothetical districts would have performed? The actual results under a different congressional map are unknowable. Federal law only requires candidates for Congress to live in the state they represent, not the district. But candidates in races around the state likely would have made different decisions on where to run, or whether to run at all.

Additionally, precinct-level analysis is not yet available for the maps never implemented for an election, and in some cases will not be as far as the 2022 election.

There was no November election in Florida’s 5th Congressional District, where U.S. Rep. John Rutherford secured re-election in the August Primary. U.S. Reps. Michael Waltz and Scott Franklin did not face Democratic challengers in Florida’s 6th and 18th Congressional Districts, districts where Rubio won by more than 30 percentage points.

At first blush, DeSantis’ map did not net seats in 2022 that Republicans would not have won anyway, though notably many have credited Republican performance down ballot in Florida to DeSantis’ coattails and policies as Governor. But MCI Maps founder Matt Isbell said the significance of the map may not be apparent in a landslide year for the GOP.

“Had a map like the Senate’s or the vetoed plan been in effect, Republicans likely would have still flipped the 13th and 7th. The 14th very likely could have been a shocking flip as well,” said Isbell, a Democratic consultant.

Republican Laurel Lee won the new House district, Florida’s 15th Congressional District, and Isbell figures a Republican candidate would have won in this year’s climate regardless. Similarly, Democratic hopes of unseating freshman Republican U.S. Rep. María Elvira Salazar this cycle would have gone “up in smoke” in any drafted version of Florida’s 27th Congressional District.

But both those seats should be competitive in future cycles, as should Florida’s 28th Congressional District, represented now by U.S. Rep. Carlos Giménez. That’s based on pre-2022 performance in the districts as much as anything

But where the maps make a difference are the places not in play. In the vetoed map, the Jacksonville-area seat where Lawson might have won would be competitive most cycles. CD 7, 13 and 14 would be more in play in a neutral climate or a blue wave year, both of which could happen in the decade that the maps will theoretically stand.

One comment

eva

December 7, 2022 at 4:32 pm

I routinely produced more than $26,380 in additional domestic revenue because of online interaction that lasted for a long time and quick replay. Actual earnings from my greatest (hbf-02) domestic sales were $18,636. Certainly, everyone can now. Utilize this to increase

…

your online income——————————➤ richestjobs85.gq

Comments are closed.