- Alex Diaz de la Portilla

- Anna Paulina Luna

- Broward County

- Byron Donalds

- Carlos Morales

- Daniel Perez

- Daniella Levine Cava

- Donlad Trump

- Express Homes

- Fabian Basabe

- FAU

- Florida Atlantic University

- Francis Suarez

- Freddy Ramirez

- Gary Johnson

- George Santos

- Harvey Ruvin

- Jacob Cutbirth

- James Comer

- Jamie Grant

- Jared Moskowitz

- Joe Biden

- Joe Carollo

- John Kelly

- Johnny Farias

- Juan Fernandez-Barquin

- Lori Chavez-DeRemer

- Luis Montaldo

- Marco Rubio

- Mario Diaz-Balart

- Marjorie Taylor Greene

- Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School

- Matt Gaetz

- Miami

- miami dade county

- Miami Herald

- Miami-Dade Sheriff

- Mike Redondo

- Nick Frevola

- Palm Beach County

- Paul Renner

- Peter Licata

- Randy Fine

- Ron DeSantis

- Scot Peterson

- Sergio Mendez

- Vickie Cartwright

- Victoria Mendez

- WLRN

Another year of South Florida politics is in the books, and it was nothing if not interesting.

Broward, Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties again drew state and national headlines for the achievements — and debacles — of public officials and the communities they served.

The process of distilling the year’s most impactful stories into a definitive “Top 10” was neither scientific nor easy. Big contenders like Donald Trump’s historic federal arraignment in Miami, Broward Sheriff Gregory Tony’s continued ethics troubles and the fallout from Heat arena name sponsor FTX’s collapse all failed to make the cut.

But we think you’ll agree the list below spotlights the especially high (and low) points of the year.

Let us know in the comments if you agree.

10. Death of Harvey Ruvin sparks local and state shifts

The New Year’s Eve passing of longtime Miami-Dade Clerk Harvey Ruvin colored the county’s first week of 2023 in mournful tones.

After 56 years in elected office, Ruvin was the most popular politician in the county, taking more votes in the 2020 election — nearly 759,000 people — than any other candidate on the ballot, including those running for President, Congress and Mayor.

Ruvin’s preferred successor, longtime General Counsel to the Clerk’s Office Luis Montaldo, took over as interim Clerk after Chief Judge Nushin Sayfie appointed him on Jan. 2.

The stint proved short-lived.

On June 9, Gov. Ron DeSantis tapped Republican Rep. Juan Fernandez-Barquin to serve out Ruvin’s remaining term through 2024. That created a vacancy in House District 118, an unincorporated strip of Miami-Dade Fernandez-Barquin had served since 2018.

Curiously, DeSantis didn’t call for a Special Election to fill that vacancy until more than a month later, after the ACLU Foundation of Florida sued to force one. Three men qualified for the race: Republican lawyer Mike Redondo, a first-time candidate, and former Miami-Dade Community Council members Johnny Farias, a Democrat, and Francisco “Frank” De La Paz, an independent.

Redondo won handily on Dec. 5 with massive support from the Florida GOP and its elected members. But questions about Redondo’s residency in the district and a plush, $1 million waterfront condo he bought 20 miles away just days before filing for the race have since raised concerns about whether he’s legally eligible for the HD 118 seat.

The condo purchase, and a 30-year mortgage Redondo signed requiring that he use it as his principal residence for at least one year, prompted Farias’ campaign to say it may challenge the election’s results.

9. Mr. Moskowitz goes to Washington

It’s been less than a year since Jared Moskowitz took his seat representing Florida’s 23rd Congressional District, and the Broward Democrat has made strong use of his time in the spotlight.

Seemingly every other week, the former state lawmaker and “Master of Disaster” has gone viral for his sharp ripostes in committee or social media posts lambasting political foes and hypocrisy he sees on Capitol Hill.

Moskowitz called out House Republicans’ “COVID amnesia” for focusing only emergency spending under President Joe Biden, reminding them that the pandemic was “a three-year event.” He blasted Marjorie Taylor Greene for prioritizing book bans over gun control with the T-shirt-ready assertion, “Dead kids can’t read.” Last month, House Oversight Committee Chair James Comer likened Moskowitz to a Smurf after he compared Comer’s family business dealings with the GOP’s case for impeaching Biden.

But it hasn’t all been contentious. Moskowitz, whose principal mission in Washington so far has been to advance gun safety legislation and awareness, has made it a point to cross the political aisle.

He stood alongside Byron Donalds in February to call for compromise between the parties in government spending. That month, he also partnered with Mario Díaz-Balart to refile the Parkland-inspired EAGLES Act.

He and U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio teamed up to replenish FEMA’s dwindling Disaster Relief Fund. He then co-authored a letter with Matt Gaetz, Anna Paulina Luna and Tim Burchett demanding more transparency on UFO accounts.

To further bolster interparty ties, Moskowitz launched an initiative to take a Republican lawmaker to lunch every week. He later co-founded a “Congressional Sneaker Caucus” with Lori Chavez-DeRemer to foster more bipartisan cooperation.

In fewer than 12 months, Moskowitz has developed a reputation among his peers for having a silver tongue — and a heart of gold.

8. Daniel Perez officially confirmed as next House Speaker

Miami state Rep. Daniel Perez had an advantage over his peers when he locked up a race in 2019 to lead the Florida House during the 2025-26 Sessions.

He was a “redshirt freshman,” a lawmaker elected in a Special Election that enabled him to serve in office longer than others in his class. That extra legislative experience typically gives redshirts an edge in leadership races.

Such was the case for current House Speaker Paul Renner, who was elected in a 2015 Special Election and whose top challenger in the 2016 class was Tampa Rep. Jamie Grant, who by then had already served two terms.

But while Perez managed to outpace others vying for the top House post, his anticipated ascension remained contingent on several variables. Among them: Republicans had to keep control of the House (hardly a tall order), and Perez had to keep getting re-elected.

That turned out to not be a problem. Perez proved himself a powerhouse fundraiser, in each subsequent race stacking virtually prohibitive sums between his campaign account and two political committees.

Since winning office, no challenger has come within 15 points of him. In 2022, no one from either major political party even dared run against him.

All the while, he delivered millions in appropriations to his district and provided a steady hand in helping Renner deliver key Florida GOP legislation, from deregulatory measures and packages designed to stabilize insurance and housing costs to supporting the Governor’s battle with Disney and passing Florida’s new permitless carry law.

By the time he was officially designated Sept. 18 as the next Florida House Speaker, it was the foregone conclusion of foregone conclusions.

It also was a win for Miami-Dade. When Perez takes the gavel in November, he’ll be the third Cuban American from the county to rule over the chamber and the fourth overall in Florida history.

7. Vickie Cartwright out as Broward County Superintendent amid School Board turmoil

Broward County swore in its third Superintendent in three years in 2023 — and the chance controversy will abate at the nation’s sixth-largest school district seems only a little less likely for 2024.

When fired in January, Vickie Cartwright was a month shy of marking her first anniversary as Superintendent. She succeeded Robert Runcie, who resigned following his arrest for allegedly lying to a grand jury investigating the state’s worst school shooting in Parkland.

A judge dismissed the resulting perjury charge against Runcie in April. But the grand jury cast a long shadow over Cartwright’s tenure.

After the grand jury report, DeSantis removed four School Board members who chose Cartwright to be the district’s executive. He then installed four hand-picked Republicans who seemed to be reading from a different book.

Before the quartet were due to step down for elected members following the November Midterm, the School Board voted to fire Cartwright. The newly elected Board reinstated her, but she then faced another firing 42 days later. New state Department of Education complaints came in alongside local grievances about her divisive leadership style.

It ended with Cartwright agreeing to leave the school district for a $267,000 severance package.

Broward Schools has been in the DeSantis administration’s crosshairs ever since it became the first to defy the Governor’s decree as schools reopened in 2021 that students could not be required to wear masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

As of July 1, the Tampa Bay Times counted 61 new Superintendents installed in four years among Florida’s 67 school districts. That doesn’t include Cartwright’s successor, Peter Licata, who is already facing controversy.

Broward will become the first district to publicly face state discipline for allowing a transgender female student to play on a high school girls’ volleyball team, a violation of a state law passed in 2021.

6. FAU presidential search’s surprises draw scrutiny

For twists and turns, few South Florida stories stand out quite like the search to replace the Florida Atlantic University (FAU) President.

Because of 2022 legislation, laws shield the identities of candidates to lead the state’s colleges and universities until the finalists are revealed, And with several of them ending up with just one finalist after that law passed, jaws dropped in July when three men were named finalists to succeed FAU’s eight-year President John Kelly — and none were named state Rep. Randy Fine.

After Fine told the media in March the DeSantis administration had approached him about taking the job, it was largely assumed that the pugnacious fighter for the Governor’s agenda was guaranteed to lead the 30,000-student school based in Boca Raton. The moving trucks were all but scheduled to deliver him to South Florida from Brevard County, it seemed.

Fine, the Legislature’s only Jewish Republican, has taken on DeSantis’ most visible culture-war fights, sponsoring laws now under court challenge that prohibit children from receiving gender-affirming care or attending “adult live performances,” to name a few.

Days after the finalists were named, though, the Florida Board of Governors suspended the search. State University System Chancellor Ray Rodrigues sent a letter to FAU Board of Trustees Chair Brad Levine raising concerns that the candidate questionnaire included an item about gender identity that could violate federal law.

An audit of the search has since called for a do-over. But Fine is not likely to be in the running this time.

When Fine wrote an op-ed in the Washington Times announcing he was jumping ship to endorse Trump for President because of the Governor’s weak response to antisemitism in Florida, DeSantis shrugged it off as Fine being mad he wasn’t going to be FAU President.

5. Fabián Basabe, controversy magnet

Republican Miami Beach Rep. Fabián Basabe was a headline machine this year, but rarely for the right reasons.

Following his razor-thin victory in left-leaning House District 106 over an experienced, better funded Democratic opponent, Basabe sponsored several bills for the 2023 Session. One passed in May.

But few were paying attention by then to the socialite-turned-politician’s legislative laurels. On April 13, CBS News Miami reported that Basabe, 45, was under investigation for allegedly slapping an aide.

Basabe’s accuser, Nick Frevola, 26, then also filed a lawsuit with former intern Jacob Cutbirth, 24, claiming the lawmaker sexually harassed and groped them.

Outside firms the House hired to look into charges found little to no evidence Basabe acted inappropriately. A lawyer for the men said both probes were biased and wrongly discarded information supporting her clients’ claims.

She announced plans for a second lawsuit, this time against the House itself.

Basabe, who once told an LGBTQ gathering, “I am a Republican, and I am a gay candidate running for office in Miami Beach,” ran last year as a moderate pledging to support gay rights, fight for police funding and infrastructure improvements.

Those voting for him looked past prior indiscretions, including an altercation with a neighbor that led to his capture by U.S. Marshals in 2020 and resurfaced reports of racist remarks and waitress-biting.

After taking office, he generally acted in lockstep with the GOP establishment, voting “yes” on bills to eliminate permit requirements for concealed firearms, expand restrictions on LGBTQ-inclusive classroom instruction and a measure known colloquially as Florida’s “anti-drag” legislation.

He has since had numerous public spats with Democratic South Florida officials and faced boos at community events, calls to resign and comparisons to now-former Congressman George Santos, who recorded a video encouraging Basabe to “hang in there and keep fighting.”

4. “Coward of Broward” Scot Peterson acquitted

For South Florida’s worst transition to obscurity in 2023, the prize would have to go to Scot Peterson.

The former Broward Sheriff’s deputy became known nationally in 2018 for hiding behind a tree as a killer unleashed a bloodbath at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The shooting rampage stands as the state’s worst school shooting and left 17 people dead inside.

Peterson, the good guy with the gun, did not step up. He became known as “the coward of Broward.”

The young gunman shown on video killing people escaped the death penalty in 2022. Perhaps that added to the hue and cry for Peterson to be held responsible. In a prosecution believed to be a national first, he was charged criminally for failing to confront the gunman — including seven counts of felony child neglect and three counts of misdemeanor culpable negligence.

Peterson stood trial in May and faced a potential of nearly a century in prison and the loss of his $104,000 annual Broward County pension.

The jury acquitted him.

After the ruling, Peterson went before the cameras and declared, “I got my life back.”

Not entirely true. He’s still being sued for his inaction. For the survivors of the victims, however, it led to some reflection on who can never get their lives back.

3. Failure to launch: Francis Suarez’s short run for President

There were rumors as far back as 2021 that Francis Suarez, Miami’s wildly popular Mayor, was mulling a run at the White House. He made it official in June, entering a crowded Republican field with a respectable war chest but far less name value than many others vying for the party nomination.

His campaign never really got off the ground. Weighed down by federal investigations into his business dealings that still pend resolution (more on that later), a bizarre artificial intelligence publicity stunt and a televised gaffe about Chinese Uyghurs that rivaled Gary Johnson’s Aleppo flub, Suarez struggled to gain support away from home.

It wasn’t for lack of effort. Suarez worked to distinguish himself from Donald Trump, the GOP race’s front-runner, by highlighting his Hispanic heritage and referring to himself as a “generational” candidate whose youth could invigorate the nation.

He took aim at DeSantis’ struggles with retail politics and restrictive abortion stance while also bashing progressives for trying to popularize terms like “Latinx,” which he described as nonsensical.

In August, he flew to Texas for a press conference at the U.S.-Mexico border to decry the Biden administration’s immigration policy and tepid response to the historic July 2021 protests in Cuba.

It was all for naught. Whether because of his insufficient renown, exclusion from national polls that may have otherwise buoyed his campaign or general lack of executive bona fides as a Mayor with scant executive powers, Suarez’s candidacy crashed and burned in just over two months after the Republican National Committee denied him stage space at the first GOP debate.

In suspending his long shot campaign Aug. 29, he became the first GOP candidate in 2024 to drop out of the race.

Suarez has seemed less than delighted to return to his existing job as Mayor. Two weeks after he left the race, he got into a heated, physical exchange outside his City Hall office and grabbed the phone of a Miami Herald reporter who inquired about his potential conflicts of interest.

Sightings of him at City Commission meetings have been so rare the Herald remarked on his attendance to one Dec. 11. And Suarez ended the year under fire — including calls for his resignation — after a deep dive from the Miami Herald about his advocacy on behalf of Saudi Arabia.

2. The fall of Freddy Ramirez

By all accounts, Alfredo “Freddy” Ramirez was as close to a shoo-in for the returning office of Miami-Dade Sheriff as any candidate for elected office in the state.

A true homegrown leader, he rose through the ranks of the eighth largest police department in the country for the better part of three decades to become Police Director in January 2020.

Mayor Daniella Levine Cava later broadened his responsibilities to include oversight of the county fire rescue and emergency services as well.

Miami-Dade hasn’t had an elected Sheriff since 1966. That will soon change due to a referendum Florida voters approved five years ago. Ramirez filed to run for the job in May and, for many, his victory was a foregone conclusion.

That was until July 24, when Ramirez pulled over on Interstate 75 with his wife in the car and shot himself in the head. He was rushed to a nearby hospital, where spent more than a month recovering from the injury.

Before the shooting, Ramirez and his wife of 28 years attended the Sheriffs Summer Conference at the JW Marriott in downtown Tampa, where witnesses said the couple fought. At least three people said they were told Ramirez pushed his wife against a wall with his hands around her throat. One witness said they saw him put a gun in his mouth.

The Ramirezes denied those claims when police questioned them at their hotel room, where they briefly placed Ramirez in handcuffs before letting him go and asking the couple to leave the hotel.

Ramirez attempted suicide not long after. He later said his wife grabbed his arm “so the resulting injury was serious but not fatal.” Neither has revealed what their argument was about, though both said alcohol was involved.

Ramirez lost an eye, but didn’t suffer brain damage, authorities said. In September, he dropped out of the race for Sheriff, which has since swelled to include 14 candidates.

Two months later, Levine Cava confirmed Ramirez would return to the department in an advisory role. He’ll be allowed to carry a gun.

1. Corruption at Miami City Hall

Miami has long been labeled a sunny place for shady people, a mecca for grifters, sharks and malefactors seeking an easy buck. In 2019, the “Magic City” — its official moniker — was ranked the fourth-most corrupt city in the country, based on an analysis of Justice Department figures.

An updated version of that report would likely place Miami a few notches higher. Before the city’s election last month, three of its six elected officials were under investigation for misusing their positions for personal benefit or vendetta.

In June, a jury found Miami Commissioner Joe Carollo liable for violating the First Amendment rights of business owners in the city who supported his political opponent, awarding the plaintiffs $63.5 million. Miami faces a separate, $28 million suit related to the case.

Local prosecutors are now looking into old accusations that several Miami politicians, particularly Carollo, improperly influenced the city police force.

Also in June, the FBI and SEC opened parallel investigations into whether Mayor Suarez improperly leveraged his public office to win project approval for a developer who paid him $10,000 in monthly consulting fees.

The Florida Commission on Ethics is delving into accusations that he illegally accepted expensive tickets to the 2022 Miami Formula One Grand Prix and World Cup. It’s also investigating whether he violated state laws by spending taxpayer funds on personal security during his presidential bid.

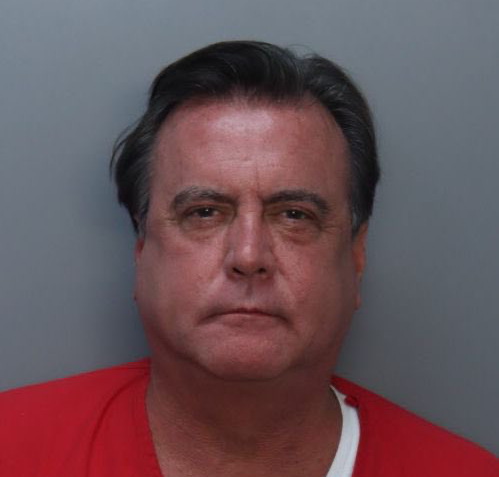

Not to be outdone, Alex Díaz de la Portilla — who lost his City Commission seat last month — was arrested in mid-September on a host of corruption charges, including bribery, money laundering and criminal conspiracy.

If convicted, he could spend the rest of his life behind bars.

Then there’s Miami City Attorney Victoria Mendez. In March, a former Miami-Dade resident sued Mendez, her husband Carlos Morales and his real estate firm, Express Homes, for allegedly using Mendez’s city connections to make a big profit on a home they bought from him at “below market value.”

That was just the tip of the proverbial iceberg, according to WLRN reporting.

WLRN uncovered 14 instances over 12 years in which Express Homes bought houses and sold the houses of elderly residents who were deemed “incapacitated” by a court had their assets placed under the control of a private, nonprofit agency called the Guardianship Program of Dade County.

In multiple instances, Express Homes flipped the houses within 24 hours for five-figure gains. Other sales took longer but generated far greater profits.

A former President of the Guardianship Program, Sergio Mendez, owned a private law firm that had a hand in five Express Homes property sales.

Suarez was involved in several transactions in his capacity as a lawyer while serving as a City Commissioner.

Suarez was also involved in planning a March trade summit in Miami Beach organized by Saudi Arabia, according to the Herald, that has since raised questions about whether he broke federal law by not registering as a foreign agent.

Two sitting Commissioners, two former police chiefs and a former Mayor have called for Suarez to resign.

____

Anne Geggis of Florida Politics collaborated on this report.